|

President's Report

Goddard College Board of Trustees Meeting

Even as external giving is at an unprecedented level, Goddard continues a systematic process of internal assessment of our operational capacity, administrative infrastructure, strategic indicators and measurements for success, and the academic quality and integrity of our degree and other programs. This Fall's Report of the College to the Board of Trustees continues to provide you with data on two strategic indicators directly related to the board's fiscal and fiduciary responsibilities: development and enrollment (which includes admissions and retention). At our last meeting, a focus on the "viability" of programs revealed the campus undergraduate residential program as a source of concern and challenge due to struggles to attract more students to the program and to keep them once they are here. While many current students and faculty attest with great loyalty to satisfaction with the quality of the existing program as it is, the enrollment and retention statistics indicate a need to reexamine the reasons for the size of the program. The program enrollment at present levels causes fiscal and budgetary instability and problems for the college, both short-term and long-term. The fact that the program's size leads to fiscal instability, a point which was stressed at the last two board meetings, is reinforced by memos I have received from Peter Casey, Vice President for Marketing and Enrollment, in the past weeks as the budget was being considered for final approval. As you know, the budget is based upon student enrollment projections, since the college revenues primarily come from student tuition (this will be less and less the case as our development capacity increases and we once again seek the validation and support of funding from grants and foundation gifts). I have Peter Casey's memos to this report. These memos give you graphic evidence of the results of having such a small size: one or two students coming or going can throw our system into budgetary and operational chaos. While another set of memos from Peter to the staff and me are included to show off and reassure you of the creativity, spirit of cooperation, drive, and willingness to think "out of the box" of our dedicated staff, we see overall how taxing it is to our staff to have to deal on a crisis basis with this situation twice a year. We see how our dependence upon a few students' decisions to come or stay results in our vulnerability as an academic institution. Taken together, these memos show just why we need to change the size of the enrollment if we are to stabilize and grow. It should be obvious that a college dealing with the fluctuating realities on a daily basis cannot be engaged in long-range and strategic planning of the campus programs. Running the program at this size keeps the program and college perpetually marginal, at the edge of crisis, having to make shortterm and compromised decisions.

Therefore we are embarking upon a systematic analysis of our program, which will coincide with our efforts to access nationwide thinking from scholars and experts on what the world knows now about itself and human capacity for learning that we did not know 60, 20, 10, or 5 years ago. It has been Goddard's original mission continuously to maintain academic degree programs of relevance and usefulness to society and individuals, through incorporating into what and how we teach ongoing advances in knowledge. In this sense we are doing an audit or inventory both of our program and of scholars' assessments of what the world knows now. For the internal review, we already have a head start with the program reviews prepared this spring by faculty and academic leadership, and we will build our assessment and audit on this work. While in the past Goddard has made drastic changes in its structure due to crises, the college is committed to a deliberate and strategic assessment and plans for stability and growth. To facilitate planned change, we have been engaged in systematic generation and analysis of data, building our professional infrastructure, building slowly and methodically our capacity for generating and analyzing data, and with greater sophistication looking at trends in our strategic indicators and their meaning. You see the fruits of this in this Report of the College. However, the internal and external studies that would indicate the academic curricular and pedagogical directions the college should take are not the whole answer. In my February 1999 Report, I discussed the reality that even if Goddard could fill the residential undergraduate program to capacity, and 100% of our students remained four years at the school, and each student paid the full tuition 2, the resulting revenue is not sufficient to allow the college to be stable or to grow. The revenue would not allow for renovation, adequate staffing, staff and faculty development, new program initiatives, technological equipment for students and administrative operations that must be updated and maintained, and campus grounds and buildings upkeep, either on a level which is expected at a prestigious liberal arts college or at all. In this report to you I noted that the critical size of the programs was dependent upon our pedagogy requiring on-campus residence and upon the residential capacity of the college. Without the Northwood campus, without the Plainfield houses, and without Kilpatrick renovated and able to be used fully, the college simply cannot get the enrollments necessary to sustain its operations at the size we need. This is true no matter how comprehensive, state-of-the-art, and brilliant we are in the quality and nature of the curriculum and pedagogy of the campus program.

The first need, to develop our residential capacity, requires a financial plan, the commitment of donors, the trust of lenders, and being blessed with a guardian angel. We need board commitment and leadership for this. The second need, a new pedagogy, requires the kind of systematic study that we are now planning to undertake through having a national task force and by embarking on a self-study by members of our campus community of what we presently know and do at the college, both of which will result in new thinking about our pedagogy. The third need, policy regarding residential capacity, requires senior staff to make this decision, with board support, and ties directly to what our pedagogy is. If the college decides it would increase access and learning outcomes to integrate distance (electronic) learning, international learning, service learning, sabbatical learning (i.e., affiliation with another program, school, or learning activity), and experiential learning into the residential experience (which Goddard has experimented with in different forms over the past decades with remarkable success), then there would be more flexibility in the use of the campus residential facilities. The requirement to live on campus would be tied to the nature and purpose of this experience. As a context for our continuing considerations of enrollment, and the need to examine what and how we teach, I am also enclosing other items for your consideration. I am formally including the article from Business Week I referred to and handed out at the last meeting. The point of this article is that it is going to be increasingly competitive to attract students in the niche market of innovative, caring, small liberal arts schools with a mission of social relevance. Dear to my heart, the article featured colleges that have turned around and are considered state of the art for their focus on interdisciplinary (e.g., a course combining physics, dance, and history), integrated, problem-based, socially oriented, outcomes-based programs that meet society's needs for the workforce and leadership of our civic culture. For this reason, I am also enclosing the written text of my opening address at the last board meeting that focused on curriculum. In this piece I urge us to consider that Goddard's niche market can derive from the mission and structure of the college, what I call its micro-circuitry for creativity, which comes out of the integration of what has been traditionally divided up into arts, humanities, technology, social sciences, natural and physical sciences, and technology. My piece asserts that Goddard's structure can be built on this integration: that we can become the place for the most ambitious, a place where genius can flourish, a place where students can remain whole, and not forfeit their diverse talents and interests to fit into the girdle of narrow curricular requirements for a traditional major. I am circulating this piece to our staff, students, and faculty as well, and I invite your and their comment and thoughts on both pieces.

Further, in theory Goddard should do well on these indicators. Goddard was designed to be different in a national context of other educational institutions: it was designed to produce better learning outcomes, a more rigorous, more relevant, more useful, more responsible education. It is supposed to do things better, by virtue of what we knew about the world and learning, getting away from factory approaches. Also, Goddard assures our accreditation agency, parents, loan officers, employers, high school counselors, and others that we provide a satisfactory education for various degrees, without the benefit of grades, or credit for courses, or requirements of courses that must be taken to satisfy the college that certain skills, expertise, and knowledge are attained. Therefore it is even more critical to make the case for how the college performs in "the real world". I would wish that learning outcomes and measurement of them would be part of the ratings, and that someday a college would be evaluated on how it moved students from one developmental stage to another (this can be quantified). But for our purposes now, understanding our progress in terms of criteria that other institutions are judged by will give us standard benchmarks. I do not think these should be our only benchmarks or criteria, but I think we must be able to claim that we excel in the categories which apply to our mission, size, and region. ' The related email is from alumnus Steve Coleman, who is doing research on higher education and wrote to ask about where Goddard is in our thinking about our mission. Again, I recommend that we use his questions as a way to organize a discussion around our mission and objectives. It seems an ideal topic for a board retreat. I believe that Goddard's board has thought deeply about our identity, and that you have been challenged by and challenge the provocative, evocative Goddard community in your thoughts. It seems to me that Goddard has always sustained a conversation and debate about our purpose, and that making clear the board point of view would be extremely helpful for college morale. Taken together, Steve's and Peter's questions weave operational capacity, academic quality, and institutional efficacy with spiritual issues of mission and purpose, and we would ground ourselves in our next critical stages by satisfying ourselves that we have faithfully addressed their questions.

The reason that I see this issue as key to our consideration of the purpose and objectives of the undergraduate campus program is that it has been defined by some members of the faculty and the students whom they have trained as overtly advancing a certain political agenda: that the purpose of the college is an "alternative, counterculture" critique of "the dominant culture", that its purpose is to "teach you that Cuba is the only democracy in the western hemisphere", "to teach you that global capitalism must be fought," and that its purpose is to promote "radical participatory [i.e., not representative] democracy". From this point of view, in which the board itself and the presidency is contested on ideological grounds, anything the college does in the way of decisions about curriculum, pedagogy, grounds, buildings, personnel policies, evaluation of the governance document, criteria for success, marketing, even being part of the U.S. News and World Report survey (which I brought to our faculty to help me fill it out according to their sense of what important criteria are for the college to be evaluated by), must be judged by the standard of its fidelity to this political agenda. Many alumni I have talked to and reflected with have told me that this is not their understanding of their education at Goddard. In any case, as we strive to determine our niche and how we will increase enrollment and retention, we need to think about how we can expand the present pool of students interested in and needing the education Goddard can produce. The way that I personally would synthesize the above points and concerns expressed by staff, alumni, former faculty, and education writers includes the following. Goddard was originated to challenge existing practices in American higher education. Its purpose was to produce a different kind of learning, which was practical and useful and relevant to society, and increased the capacity of the student to make a difference in the world. Its appeal to remarkable, creative, mature, and motivated students was that its approach is singularly student-centered. In molding itself to fit the needs of society, the college departed from an "Ivory Tower" approach in which the word `academic' is understood to mean "not real world, impractical, not worldly, not realistic". It followed that the college continued to evolve in ways that increased the opportunity of students to gain their degree, including the nation's first low-residency programs for adults. In the sense that the student is at the center of the learning experience, and that more than the traditionally privileged should be able to attend, the college was a democratic alternative to rigid formalistic places where students were told what to take, when to take it, and were expected passively to mirror what professors said. Moreover, the emphasis on faculty-student interaction, supported by a system of advising, broke down traditional

I personally believe that a liberal arts college should expose students to a great diversity of intellectual experiences across the disciplines in such a way as to enable students to connect and see as coherent the various expressions of reality of this world. Students should be exposed to a multiplicity of ideas from faculty, staff and other students about the world-perspectives, worldviews, cultural views, and political views. There should not be any one agenda to promote, but rather, a profusion of views expressed, vigorously debated. There should be continuous intellectual ferment. Arguments should be made over how to represent the new science, or new linguistics, or new literary criticism, into the curriculum, into pedagogy. We should be trying out multiple experiments to model these ideas. We should be characterized by diversity of disciplines, cultures, and identities. I believe that faculty should be able to let their views be known, but that there should be dozens and dozens of views expressed on each of these subjects, each passionately argued, to show students how diversity does not threaten but defines a vital learning community, how pluralism works, and how to develop influence and impact in a learning community. I believe that once we turn our heads to the environment around us, and see the tremendous advances that have been made in the sciences, social sciences, technology, and in the arts and humanities, that the opportunities for Goddard to reassert its primacy in integrated, interdisciplinary, meaningful and essential education will be abundant. The needs for education which combine international, environmental, service learning are great. I see a future in which the great instability of the college is intellectual, with verities having a short shelf life, inert ideas becoming volatile with exposure to other disciplines, and creativity flourishing. I see a future in which how Goddard evolves once again a residential undergraduate program that is state of the art makes Goddard continue to have a leading role in teacher education. Recent articles in the nation's newspapers have stressed how students of high school age will increase 15% in the next 9 years, with increased calls for more teachers, especially of the sciences and math. In this "Baby Boom Echo", where teacher training will be called for and millions more students will be seeking to entering higher education, as well as when the increased numbers of the aging population will demand more higher education (see Boston Globe article), there will be increased need for a liberal arts education that connects how and what we educate, especially one that connects learning to the great themes of the next century. These themes revolve around the interdependence of all systems from chemical, physical, cultural, economic, political, and biological points of view, with technology being the connective tissue, enzyme, catalyst, and circuitry of these systems. Translated for education, that means that international education, environmental education, service learning, and education which shows the essential interrelationship of technology and traditional arts and crafts, and communications, will be what is called for. The innovative programs Goddard-style (student-centered always, tutorials, reflective

Goddard's many degree programs and the programs we are striving to develop to provide more access to Goddard education, and more real-world experience for our students, provide an arena for continued experiments, innovations, and responsiveness to what the world needs now. At home, we need what the world at large needs, the ability to engage in civil discourse, to encourage diversity and not see difference as a threat that must be eradicated, to respect the fact that in a pluralistic learning community there are many points of view, conflicting, contradicting, overlapping, merging, fragmenting, in countless new variations of coalitions, alliances, and estrangements. To see conflict is also to see vitality. Engineers would tell us that the tension in bridge construction makes for the strength that connects two points. Out of the many ideas, we have options for programs, new formats, experiments, and it is not an either/or situation. As Walt Whitman said, "Do I contradict myself? Very well, I contradict myself/I am large/I contain multitudes." Goddard is conceptually large enough to contain multitudes. Our challenge is to make sure that we axe "large" enough to have the critical size so that we have the resources and stability to be as bold, as free, as creative, as new, as imaginative, and as resourceful as humans know how to be. My next Report of Goddard College to the Board of Trustees will be in 2000. As Goddard crests the millennium, it is practical and encouraging to reflect on all the changes that Goddard has undergone since the 1800s, and how it remains itself as the country and world goes in and out of wars, depression, inflation, unrest, political see saws, turnovers in leadership, and wildly fluctuating ideas of what makes a just and worthwhile life. Goddard has endured continual challenge from without and within, and in all its changes and responsiveness to society's needs has remained grounded in its own special character, a character that draws and holds your commitments, that is worth your time, thoughts, and energy. Speaking for the college and myself, I am grateful for the difference you bring to our work, and that you make.

Barbara Mossberg

1. For example, a comparable institution to Goddard College, with a similar approach to learning and at least a third larger in size, offers international programs (19% of 1998 graduates studied abroad) and 240 courses per year in such topics as: American Studies, Anthropology, Art History, Astronomy, Biochemistry, Biology, Ceramics, Chemistry, Classics, Computer Science, Cultural History, Dance, Development Studies (in the World Studies Program), Economics, Environmental Studies, Film/Video Studies, History, Languages, Literature, Mathematics, Music, Painting, Philosophy, Photography, Physics, Political Science, Psychology, Religion, Sociology, Theatre, Visual Arts, and Writing.back to text 2. The following shows the residency housing capacity at Goddard College (information provided by Jennifer Carlo, Dean of Students). Jennifer notes this assumes that Rooms 3, 6 and offices are used as singles because they are smaller than the other rooms:

Aiken 6 double rooms, 2 single rooms 14 people

Dewey 6 double rooms, 2 single rooms, 1 office 15 people

Doolin 6 double rooms, 2 single rooms, 1 office 15 people

Fisher 6 double rooms, 2 single rooms, 1 office 15 people

Froliecher 6 doubles, 2 singles, 1 office 15 people

Giles 6 doubles, 2 singles 14 people

Hollister 6 doubles, 2 singles, 1 office 15 people

Pratt 5 doubles, 2 singles 12 people

Stokes 6 doubles, 2 singles, 1 office 15 people

Weinstein 6 doubles, 2 singles, 1 office 15 people***

*** pending renovation

TOTAL VILLAGE CAPACITY -145 people

As indicated by Peter Casey, Vice President for Marketing and Enrollment Management, the retention rate of Goddard students is approximately 29% of students entering from high school and 57% of transfer students.

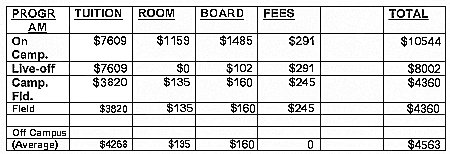

REVENUE PER SEMESTER

No student at Goddard pays full tuition and, of the discounted tuition, only a percentage of those pay tuition, room and board, thus reducing further the revenue. In summary, at this scale, even if we were striving to attain full capacity (defined by present practice and policy), the resulting revenue is still insufficient for stability and growth of the college.

|