|

Richard Schramm

I came to Goddard in 1991 because of its tradition of progressive education and democratic experimentation. I have found an educational philosophy and practice here that is truly remarkable and a commitment to education and teaching that overshadows anything I have ever experienced at traditional universities. Goddard has a strong faculty and some of the best students I have ever encountered (along with a few of the most irresponsible, but then this is my first time teaching undergraduate students). While I have been extremely pleased with the educational philosophy and the quality of teaching at Goddard, I have not been as impressed with Goddard's efforts to operate as a participative and democratic college. In fact, the authoritarian forces operating at Goddard put some of my former university settings to shame. It is these forces that I want to discuss with you as board members because much of the difficulties Goddard faces in becoming more democratic stem from the structure and operations of its board of trustees. This Fall I am facilitating a group study entitled "Business and Democracy at Goddard" which is looking at Goddard's success as a business and as a democratic organization. I would like to report our preliminary findings on the second topic: Goddard's success as a democratic organization. These are only preliminary - we still have much to do, including comparisons with other progressive colleges - but they at least identify some of the forces that are inhibiting the full development of Goddard as a democratic college. We have found ample reason for Goddard to be a democratic organization. First, democracy is what Goddard claims to be all about. From its mission statement: "[Goddard's] mission is to advance the theory and practice of learning by undertaking carefully planned experiments based on the ideals of democracy, and on the principles of progressive education developed by John Dewey and those who worked with him ...." Goddard itself could well

Second, democracy, especially participative democracy, is good education. Peter Bachrach and Aryeh Botwinick, in Power and Empowerment: A Radical Theory of Participatory Democracy 1 write that "The underlying premise of participatory democracy -- in contrast to liberal representative democracy -- is that participatory democratic politics encompasses self-exploration and self-development by the citizenry. In sharp contrast, liberal doctrine conceives of democracy as merely facilitating the expression of perceived interests, not in helping citizens discover what their real interests are." Goddard stresses learning from experience and participatory democracy offers active experience in shaping your own world and learning from the process; Goddard stresses self-directed learning, which is inherently participatory democracy. In practice, however, Goddard College is a far cry from being a democratic organization. Its long history of faculty, staff and student dissatisfaction with the standing president is a symptom of ineffective shared decision making, and of a contradiction between democratic values and managerial structures and styles. A similar contradiction is the continuing attempts at participatory decision making at some levels, while critical decisions of policy, budget, and hiring and firing remain the province of a relatively few, and these few are not accountable for the most part to the larger college community. Our group study identified the following reasons why Goddard College isn't operating effectively as a democratic/participative organization:

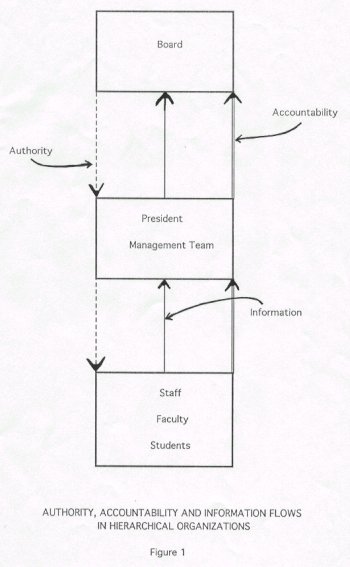

Figure 1 illustrates how these barriers operate at Goddard to inhibit the growth of democracy and effective participative decision making. Goddard is currently organized hierarchically. At the top is the board and its executive committee, in the middle is the president and his "management team" (which is also a majority of the college executive committee), at the bottom is the staff, students and faculty. Authority flows from the board to the president, and from there to the rest of the organization; accountability flows in the opposite direction. Faculty and staff are accountable to the president, the president is accountable to the board, and the board, with 80% at-large membership elected by seated board members, 2 is accountable to no one but, perhaps, themselves. or, perhaps, to some vague notion of "fiduciary responsibility." Certainly not to the college community in any direct way. Finally information flows largely from bottom to top through the president, with little information flowing down and virtually no communication between the board and faculty, staff and students. The only formal link between the board and the college community is through the 4 elected board representatives (out of a full board membership of 25). None of these college representatives is currently on the-board's executive committee. This is clearly a very undemocratic organization. Some participative decision making goes on among faculty, students and staff but the domain for such decisions is defined by the president and the board. Being accountable to the president while the president is not accountable to you creates a power difference that inhibits shared decision making. This would be remedied if the board were in some way accountable to the college community. However, the board composition of 80% at-large members elected by

|

|

|

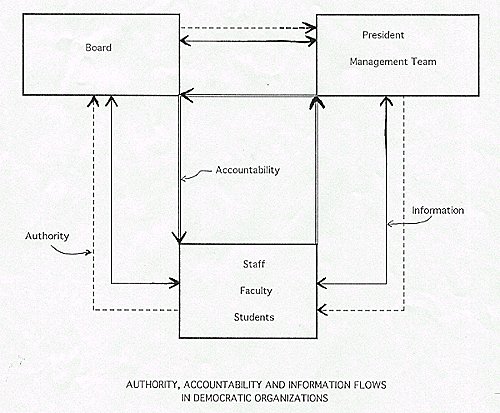

Moving from 80% at-large, board-selected trustees to 100% college-elected trustees, when combined with other needed changes in structures, processes, leadership, etc., should result in the changes in authority, accountability, information, and management needed for a democratic college. other combinations of at-large, board-selected and college elected, say 50:50, would move in this direction while still allowing inclusion of outside trustees with other resources and ideas. What does this analysis suggest for building democratic decision making at Goddard, and the role of the board of trustees? First, since there are so many interconnected parts of the problem, we need to redesign all elements of the organization in a common direction, not just try to change one or two of the pieces. We need to take steps to build a longterm, widely-shared commitment to a democratic Goddard College and to institute the changes needed to make a democratic Goddard a reality - improve board and other governance structures, institute needed organizational processes, educate ourselves about democratic management, and change leadership styles and methods. Second, because of the longterm and multi-dimensional nature of transforming Goddard into a democratic college, the board needs to play a fundamental role. Towards this end, the board needs to pass a resolution supporting the building of democracy at Goddard (perhaps moving Goddard to a democratic college within 3 years). In this resolution the board should take steps to develop such a plan, including a revised governance structure, information policy, needed organizational processes, democratic management education policy, etc.

Endnotes 1. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992, pp. 10-11. 2. The full board is a body of 25 people, 20 of whom are elected at-large by seated trustees and serve five year terms. They represent themselves; some have familiarity with Goddard as previous students. Of the remaining five, two are elected from a faculty of 70 and an administrative staff of 50 to serve three year terms; two students are elected for one year terms, one by an on-campus student body of 130 and one by an off-campus student body of 350; and, finally, one representative is elected by an alumni/ae body of 8000 (of which maybe 100 are active) for one year term. 3. This analysis was provided to the group study by Marty Zinn, co-founder of Worker-Owned Network (now ACEnet) and teacher in the Goddard Business Institute. 4. Peter Block writes in his book, Stewardship, about this form of accountability. "Stewardship in an institutional setting means attending to the service brought to each employee, customer, supplier, and community. To be accountable to those we have power over. This is accountability congruent with the redistribution of power, privilege, and purpose."  |