GODDARD CHANGES DRASTICALLY, BUT STAYS VIABLE

PLAINFIELD -- The road to recovery for Goddard College has been a torturous one,

full of blind turns and obstacles that repeatedly put the school on the brink of collapse.

The past two years have required painstaking, and often painful, decisions that

have brought drastic changes to the experimental, progressive liberal arts institution.

College President Jack Lindquist would like to think he has helped steer the college

along a course that will assure its survival.

A recent decision by the New England Association of Schools and Colleges brought a

breath of life into Goddard, which has been struggling to convince prospective

students, as well as creditors, guidance counselors and financial aid institutions,

that it can make a comeback.

The association agreed to remove Goddard's two-year probationary status, meaning

the college for the time being is not threatened with loss of accreditation.

"That decision tells the world this isn't a place that's shaky and isn't a

good bet. It says this is a place that is getting its act together," Lindquist said.

A decision to lift its accreditation probably would have meant the end of the

44-year-old institution.

"Frankly, we probably would have closed the college and tried to reorganize,"

Lindquist said.

Lindquist, 41, former academic dean of the college, took over as president in

May 1981 after a series of tumultuous events.

Three administrators, including the president, John Hall, resigned. The next

president, Victor Loefflath-Ehly, resigned a year later. With the impending threat

of financial collapse, faculty and staff worked without pay for three weeks to help

keep the college alive.

With a debt of nearly $3 million, further sacrifices were unavoidable, according

to administrators. Four of Goddard's programs were sold to Norwich University and

Vermont College, and a large part of the campus was put up for sale. A large portion

of the faculty was laid off, and the college administration was slashed.

A student who attended Goddard during the 1960s or early '70s would find a very

different institution today.

Where there were once as many as 1900 students, there are now 153. Two years ago,

the enrollment was about 1000, Lindquist said.

The general perception of the college was that it had overextended itself in

the 1960s, and it scaled down its enrollment drastically, Lindquist said.

That did not require much weeding out at the admissions office, where applications

had dropped off almost completely.

When the New England association decided two years ago to recommend that

accreditation be lifted, newspapers nationwide reported the accreditation actually

had been lifted.

In fact, Goddard successfully appealed the recommendation and its accreditation

remained intact, although the facility was placed on probation.

But the image of a broken college remained, and still haunts the school.

"Our enrollment just stopped then," Lindquist said. "Our public image was that

the school had been closed. When I showed up at conferences with the name tag that

said Goddard, people looked confused and say, 'is that the Goddard that closed?'" he said.

In the fall 1980, Lindquist was hired as a consultant to a five-member task

force given the uneviable task of "total reorganization in one year," he said.

He was named acting president in May 1981.

While the 1960s and '70s represented a period of great growth for the institution,

the 1980s will be a time of pared-down enrollment and a streamlined administration,

Lindquist said.

"Our current plan is to move back to 250 to 300 students and stay there,"

Lindquist said. "We feel it's a much more effective institution at that number,

and better educationally."

When he took over the presidency, Lindquist said even he had doubts about the

college's survival. While that is by no means certain, he now believes the college

is on the road to recovery.

"It's going to happen. The accreditation solidifies that," he said. "But it

isn't going to happen easily. There will be some delicate times as we nurse it

along... and a lot of work needs to be done to improve the public image."

One way the college has been combating soaring energy costs is by encouraging

students to work on independent studies off campus. Only a third of the student

body lives on campus; the rest are scattered across the globe, doing research

projects, writing books, were doing other creative pursuits.

Lindquist said the financial benefits are not the only reason the college has

encouraged the nonresidency programs.

"Progressive education has always had its roots in integrating working and

learning," he said. While many view a liberal arts education has an impractical

luxury, a progressive education can be as practical as any, Lindquist said.

"During a recession, many people are concerned about getting jobs, and so in many

ways, an education that involves working in the 'real world' is more practical," he said.

Novelette Stewart, a Goddard junior, said that throughout all the turmoil the

college has been going through, students remained committed to the institution.

"At Goddard, you have a very unique set of students who stuck together when we

didn't know if we'd be open from one week to the next," she said.

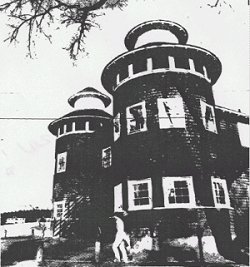

The Silos. The student body has shrunk to about

one-tenth its former size, but students say the

Plainfield college will live on.